N.B. – This was published in the December 7, 2009 issue of JoongAng Daily, an English newspaper based in Seoul, where the Philippine Resource Persons Group (PhilRPG) has a weekly column (Pinoy Voices). The full text of my article may also be retrieved from http://joongangdaily.joins.com/article/view.asp?aid=2913540.

Thirty journalists were killed last month in the worst act of election violence ever in the Philippines. Their deaths are another way of restricting freedom.

Thirty journalists were killed last month in the worst act of election violence ever in the Philippines. Their deaths are another way of restricting freedom.

There is a difference between freedom of speech and freedom after speech. Filipino journalists know this all too well.

Unlike other Asian countries, Filipinos and Koreans are said to enjoy freedom of the press. However, even if colonialism helped shape the nature of journalism in the two countries, there is a marked difference in the practice of journalism in the Philippines and Korea.

Many journalism schools highlight the Philippine press as the freest in Asia. Major textbooks on the history of Philippine journalism stress that this is due to the constitutional guarantees of basic freedoms, as well as other laws that uphold press freedom like the Shield Law, which protects journalists from revealing their sources.

Even international organizations recognize the freedom Filipino journalists have. According to Freedom House, the Philippine media is “among the freest, most vibrant and most outspoken in Asia.”

On the other hand, a study by Press Reference (www.pressreference.com) shows that Korea is a “media-rich country,” having 116 daily newspapers, 121 television stations and 209 radio stations. For every 1,000 Koreans, it is estimated that 331.9 have television sets, 177.4 have cable subscriptions, 991.6 have radio receivers, 234.9 have computers and 397.5 have Internet access.

It is not surprising that media-related statistics in the Philippines, a developing country, pale in comparison to Korea. The Philippines only has 42 daily newspapers, 31 television stations and 659 radio stations. For every 1,000 Filipinos, only 44.7 have television sets, 138.8 have radio receivers, 17.9 have computers and 24.1 have Internet access.

In assessing press freedom in both countries, it is interesting to note that the Philippines is rated by Freedom House as “partly free,” while Korea is said to be “free.”

Freedom House grades 195 countries and territories from 0 (best) to 100 (worst) based on a set of 23 questions divided into three categories – legal environment, political environment and economic environment.

Based on its explanation of the methodology, “[a] score of 0 to 30 places the country in the Free press group; 31 to 60 in the Partly Free press group; and 61 to 100 in the Not Free press group.” In its 2009 survey, the Philippines earned a score of 45; and Korea, 30.

It is interesting to note that the Freedom House 2009 study considers Iceland, Finland and Norway as having the freest presses in the world, while those with the worst press freedoms were Burma, Turkmenistan and North Korea.

Just like the Philippines, the Korean press is considered “noisy, vibrant and powerful” and enjoys constitutionally guaranteed freedom. But unlike in Korea, where the modern press traces its beginnings to the waning days of the Joseon dynasty in the 19th century, the Philippine press started during the era of Spanish colonialism in the 16th century.

In its analysis of the Korean press, Press Reference highlights its role in the struggle for independence against colonial rule, even if there were also compromises made with the ruling powers.

“Enlightening the public was the primary objective of the press,” the site writes. “When Japan colonized Korea in 1910, weeklies turned dailies, and privately owned dailies began to play the role of educators and independence fighters. Many of the then reporters and editors themselves conceived of their role in that way. For survival the press learned to compromise with the colonial ruling powers during the years between 1910 and 1945. This legacy served the Korean press very well after Korea’s independence in 1948 and during the subsequent despotic and military regimes in the 1960s through the 1980s.”

Starting with the 19th century publications La Solidaridad (Solidarity) and Kalayaan (Freedom), the alternative press grew vibrant in the Philippines as well, even as the Americans and the Japanese colonized them. The Filipino struggle for meaningful change continued even after 1946 when the United States granted independence to the country. As a result, alternative publications still exist, and some of them have even maximized their use of new media by creating their own Web sites and accounts with social networking sites like Facebook.

The 1987 Philippine Constitution’s Bill of Rights (Article 3) clearly guarantees freedom of the press. Section 4, for example, explicitly states: “No law shall be passed abridging the freedom of speech, of expression, or of the press, or the right of the people peaceably to assemble and petition the government for redress of grievances.”

Section 7 has a provision that reads, “The right of the people to information on matters of public concern shall be recognized. Access to official records, and to documents and papers pertaining to official acts, transactions, or decisions, as well as to government research data used as basis for policy development, shall be afforded the citizen, subject to such limitations as may be provided by law.”

The killings of Filipino journalists, however, continue unabated despite these constitutional guarantees. This problem is practically nonexistent in Korea. The U.S.-based Committee to Protect Journalists has no record of Korean journalists being killed since it started worldwide monitoring in 1992.

The CPJ, however, has listed 38 Filipino journalists killed since 1992 as a result of their work as journalists. There are 27 others listed, but the motives behind the killings were not clear. Quoting from CPJ’s methodology, “When the motive is unclear, but it is possible that a journalist was killed because of his or her work, CPJ classifies the case as ‘unconfirmed’ and continues to investigate.”

These data from the CPJ do not include the 30 journalists and media workers who were killed in the line of duty on Nov. 23 in Ampatuan, Maguindanao, located in the southern Philippines. This is said to be the worst-ever election-related act of violence in the country. CPJ said in a Dec. 3 statement, “By far, the killings in Maguindanao have proven to be the worst we have on record, and most likely the worst in the history of journalism.”

This single act of violence claimed a total of 57 lives – journalists were killed with relatives and supporters of a local politician on their way to file his certificate of candidacy as governor; others killed were only motorists who passed by when the convoy was blocked. It has been denounced internationally.

At the start of its annual meeting on Dec. 1 in India, Gavin O’Reilly, president of the World Association of Newspapers and News Publishers, said that the killings were “an act of savagery that has written one of the blackest pages in the history of the world’s press.”

Korean journalists are strongly encouraged not only to write about what happened in the Philippines but also to provide messages of solidarity to Philippines-based media groups. They are also welcome to write letters of concern to the Philippine government demanding swift justice for those who were murdered.

That there are laws protecting press freedom does not mean that all is well in the Philippine media.

While it is true that there exists freedom of speech, freedom after speech is another matter.

*The writer is a visiting professor at Hannam University’s Linton Global College in Daejeon.

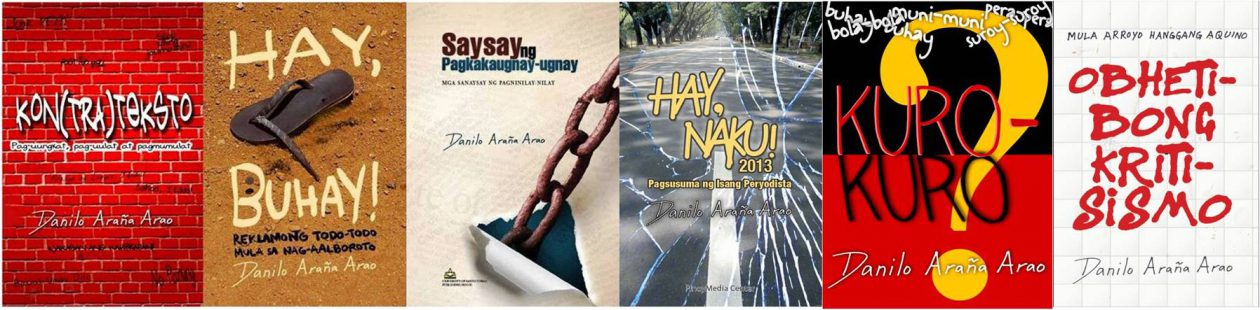

by Danilo A. Arao