The title of an Inquirer.net article today (November 27) says it all: “Peso seen reaching 38 per dollar in ’08.” The article actually cites a projection by Banco de Oro-EPCI chief strategist Jonathan Ravelas who argues, “Strong OFW [overseas Filipino workers] remittances, along with portfolio flows, will help keep the currency on the stronger side.”

This projection is consistent with the currency forecasts of BNP-Paribas, one of the largest international banking networks. Please feel free to analyze the data below.

From the data above, you will notice that even a big international banking network projects the peso to be pegged at P30 per US dollar by the fourth quarter of 2009.

With the exception of Hong Kong, there appears to be a general strengthening of the foreign currency exchange rate in other Asian economies until 2009.

Believe it or not, I fully support a strong peso. That’s not to say, however, that this is a sign of an improving economy. In analyzing the country’s economic history, we all know the complications brought about by our dependence on the United States in terms of investments and trade and its control over our vital industries.

In the short term, I believe that a strong peso can provide enough justification for consumers to demand lower prices of goods and services. In studying basic principles of economics, we are aware that a strong currency theoretically translates to lower cost of imported goods and services. Given the country’s import dependence (to the point where most of our goods and services have imported content), we should see a general decline in prices.

Families of overseas Filipino workers (OFWs) may not welcome a strong currency since this would mean less pesos to be exchanged for the precious dollars sent by their loved ones.

However, a weak currency that results in more pesos in exchange for dollars will also give rise to increased prices of goods and services, most of which are imported. This means that whatever increase they would get from a weak currency will be negated, at least in the immediate future, by higher cost of living.

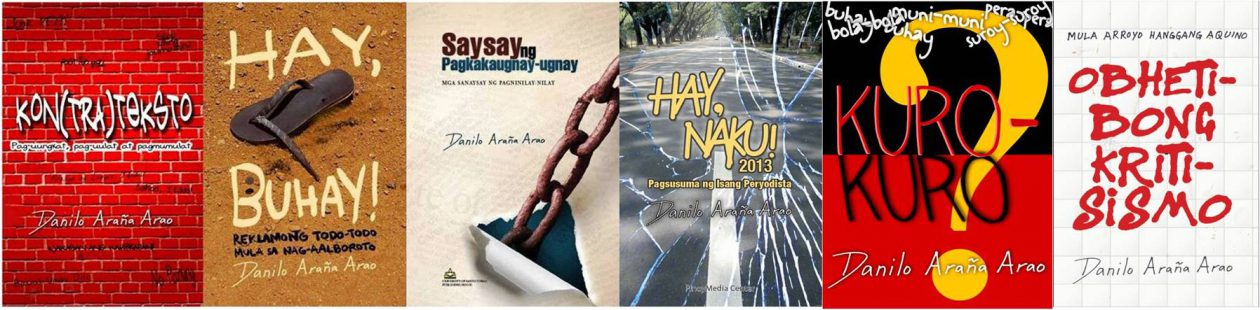

The exchange rate also has a direct effect on fiscal management. For more details, please read the two articles I recently wrote in Filipino for Pinoy Weekly on the strengthening of the peso: “Ang `problema’ ng lumalakas na piso” (Aug. 16-22, 2006) and “Sana’y lumakas pa ang piso at bumaba ang presyo” (Nov. 21-27, 2007).

Your comments will be greatly appreciated. Thank you for reading!

I too would like a strong peso by it will affect a greater majority in a distressing way. With so much dollar flowing in, inflation sets in as well. Globalization had adversely affected our economy. It is in fact shrinking as a consumer-driven economy does not generate jobs. Investors only park their money here until a better yield turns up somewhere else. Our industries are not expanding but in fact transferring elsewhere. San Miguel in fact is looking at our neighbors to put up more plants, further driving unemployment up.

The high cost of living here cancels out the increase in remittances. With less purchasing power, I wonder how our people will cope with it. High taxes do not help as the government spends our funds irresponsibly. With corruption institutionalized, our people will actually suffer more.

With 25 mining firms operating now and another 36 waiting in the wings, we might mine our country to extinction. We could end up like Nauru, a nation without a country. The social cost of migration and total disregard for the environment will soon catch up and we could end up losing more than gaining a little.

Reply: Thanks for your comment. People may not immediately feel the impact of a weak currency but it will happen eventually. However, the problem with the economy right now is that under a deregulated regime, industrialists can adjust prices whenever they want. In other words, a strong currency does not guarantee lower prices at present. The downstream oil industry is a glaring example: Despite the strengthening of the peso, prices of petroleum products continue to increase. Of course, the crude oil prices in the world market are used as an excuse, but that doesn’t take away the fact that we should nationalize instead of deregulate the downstream oil industry so that we won’t be directly affected by negative and unexpected developments in the world market. Good point about Nauru: What comes to mind right now is Ecuador which was forced to abolish its currency and is now using the US dollar. it came to a point where the ecu was so devalued that its government had to do away with the currency to arrest runaway inflation.

I’d just like to share our discussion in Econ 190.2 under Prof. Diokno-Sicat which has a different perspective on this topic.

For a developing country like ours, a “strong currency” is actually a bad thing in the sense that our export manufacturing industries would produce products that are more expensive compared to the goods of other nations, making them less attractive to foreign consumers. (Less demand, less profit, incurring losses and might end up as a death sentence to business). China and Japan are examples of countries who would love to keep their currencies “cheap” so that their exports would remain competitive in the global market. If this continues we might lose one of the only strong local industries left in the country.

Secondly, if we make imports even cheaper due to lower exchange rates, then people would have less reason to buy Filipino products given our colonial mentality. The public’s spending that would be placed on this imported goods could have gone to Filipino industries that if given the chance and the market to succeed could have helped our economy to become independent.

Considering this strengthening of our Peso is not brought about by our country’s development but carried by the remittances of the OFW’s, we are highly dependent on other countries. If they start limiting the number of workers again for whatever reason like war and safety concerns, or if they start feeling threathened from the presence of too many immigrants, then what will happen to our economy?

-=-=-=-=-=-=-

Although part of me is glad that our peso is strengthening so that it could offset the impact of the rise of imported materials(like oil, manufacturing materials, etc.) which our country could not do without, I am just wondering how our economy would turn out in the long run

Reply: Your professor apparently adheres to a neoliberal view of development which operates on the assumption that a strong currency is always detrimental to an export-oriented economy like ours. A strong bias for exports, after all, requires a weak currency so that current exporters can profit more and other industrialists would be encouraged to venture into exports. What will happen then to the goods and services for local consumption? Just like agriculture, local industries are bound to die because of the preference to strengthen exports. Indeed, developing the country’s comparative and competitive advantage is being done at the expense of the domestic market. I agree with your view that having a strong currency could encourage the consumption of cheaper, imported products which we have to guard against. But this can be solved by strengthening domestic industries through incentives and subsidies, lowering (if not eliminating) indirect taxes on local goods and services and imposing import levies, among many other protective mechanisms. This means that we should not harbor any illusion that a strong currency can solve the country’s plethora of socioeconomic problems. Thank you for your post.

I fully agree with your views. I would suggest a centralized wholesaler for oil. OPEC said that it is surprised by the high crude prices when their finance officers put the price/barrel at $64. The problem lies in speculators. With Brunei and Dubai draining their wells dry in 10 years, some quarters are trying to make the most out of their investments. Brunei and Dubai, I suspect are in collusion with investment institution to drive the prices up to make the most out of their oil.

OPEC said that demand did not increase despite China’s development and supplies remain stable. We should do away with the middlemen and directly deal with OPEC members. Marcos actually did this during the oil crisis of the ’70s.

I totally agree with Mara’s points. Remittances play a very big role in our economy today. The problem lies in our early push for globalization without strengthening our domestic industries and market. This is the reason why we continue to lose industries and businesses. While our competitors were able to put up safety nets for their industries, we did not. Be all believed in GMA when she pushed for our entry in the WTO back when she was still a senator. Looking back now, we should have studied it more comprehensively back then.

Reply: Centralized procurement of crude oil and refined petroleum products is actually a component of the nationalization of the downstream oil industry which you and I have been pushing for even before oil deregulation started in 1996. I agree that this can help forge bilateral agreements with oil-producing countries where we can get better terms. It also becomes possible for us to engage in “commodity swaps” where we would not be required to pay in dollars. It’s good that you mentioned Mara’s points about OFW remittances: In theory, a strong currency discourages labor migration as workers would opt to just stay in the country. Of course, the situation can be very detrimental to the poor majority if there are no job opportunities here. Labor migration would therefore still remain a situation of force majeure. Clearly, the country’s future rests not only on strengthening the currency but also radically changing the economic direction.