N.B. – This was published in Vol. VIII, No. 36 of Bulatlat (October 12-18, 2008), the full text of which may also be retrieved from http://bulatlat.com/main/2008/10/12/oil-deregulation-minus-the-jargon/.

Deregulation is quite simple but the powers-that-be tend to provide complicated explanations in claiming that it should be given a chance to work despite what is happening in the world market. Indeed, a clear understanding of oil deregulation leads one to oppose it, especially at the onset of unabated oil price hikes and inconsequential rollbacks.

Deregulation is quite simple but the powers-that-be tend to provide complicated explanations in claiming that it should be given a chance to work despite what is happening in the world market. Indeed, a clear understanding of oil deregulation leads one to oppose it, especially at the onset of unabated oil price hikes and inconsequential rollbacks.

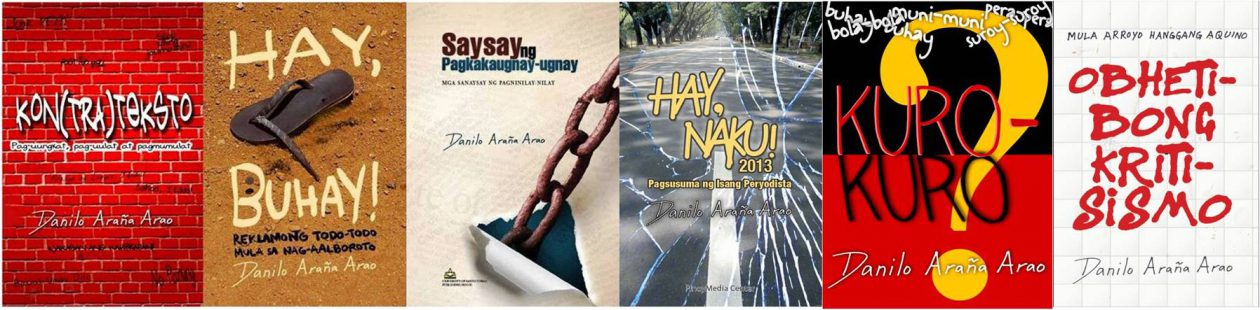

BY DANILO ARAÑA ARAO

Stripped of all the technical jargon, the deregulation that is characteristic of the downstream oil industry is very easy to understand.

In order for the economy to progress, there is a need to remove all barriers to free competition. The government should not directly compete with local and foreign investors, hence the need to sell to the private sector (i.e., “privatize”) government-owned and controlled corporations (GOCCs) like Petron which competes with private companies like Shell and Chevron.

Unlike in the past, the deregulated regime allows any industrialist to invest in the downstream oil industry. Data from the Department of Energy (DOE) show that there are 601 new industry players competing with the so-called Big Three – Petron, Shell and Chevron.

In removing the regulations that used to prevent free competition, government officials and neoliberal thinkers expect the empowerment of consumers. They argue that under a deregulated regime, consumers are “empowered” in the sense that they now have more choices. If in the past there were only three companies, there are now hundreds to choose from.

For those who believe in the principle of globalization (of which deregulation is one of the tenets, the other two being liberalization and privatization), the measurement of “consumer power” is defined along the lines of increased choices. (i.e., “If the consumer has the choice, the consumer has the power.”)

More companies mean “better and freer” competition which would then result in lower prices and better services for the consumers. The tendency of the capitalist, according to those who argue for deregulation, is to attract as many customers as possible in whatever ways necessary, like creative advertisements, substantial discounts and, of course, lower prices.

The deregulation of the downstream oil industry started in April 1996. The prices of gasoline and diesel then were P9.50 ($0.185 at the 1996 exchange rate of $1=P51.31) and P7.03 ($0.13) per liter, respectively. As a result of oil price hikes in the years that followed, gasoline and diesel reached more than P60 ($1.33 at the July 2008 exchange rate of $1=P44.956) and P50 ($1.11) per liter.

There have been rollbacks since August but these are said to be not enough based on the prices of Dubai crude and the peso-dollar exchange rate. The table below illustrates this point.

It is easy to argue that we currently live in an “abnormal” situation due to the continued increase in the price of crude in the world market. The weekly average Dubai crude, for example, reached its highest last July 4 at $137.27 per barrel. As of September 26, it is pegged at $96.68 per barrel.

However, one notices an even more abnormal increase in the pump price of diesel, widely consumed by the transport sector, relative to the increase in Dubai crude.

Twelve years have passed since the implementation of oil deregulation and the only positive effect it had was on the profits of oil companies and increased tax collection of the government, especially with the increase of the value-added tax from 10 percent to 12 percent and its expansion in 2005 to include petroleum products. For 2008, the Department of Finance expects a collection of P73.4 billion ($1,543,443,519 at the October 10, 2008 exchange rate of $1=P47.556) from the VAT on petroleum products.

Why did the expected lowering of prices of petroleum products not happen in a deregulated regime? Unlike others, petroleum products are said to be “demand inelastic.” This means that the demand for such products is not affected by fluctuations in prices because these are needed by the public.

The transport sector, for example, absolutely needs petroleum products to continue with its operations and it will always procure such products regardless of the price.

In my independent monitoring of the prices of petroleum products, what Petron, Shell and Chevron normally do is to take the lead in increasing prices and the industry players would follow afterwards. The different oil companies normally maintain only a price differential of P0.50 per liter.

Deregulation is quite simple but the powers-that-be tend to provide complicated explanations in claiming that it should be given a chance to work despite what is happening in the world market.

Indeed, a clear understanding of oil deregulation leads one to oppose it, especially at the onset of unabated oil price hikes and inconsequential rollbacks. (Bulatlat.com)

This is a shortened version of the paper presented by the author at the 30th anniversary lecture of IBON Foundation last October 7. His slide presentation (in PDF) may be retrieved from http://www.dannyarao.com/files/arao-downstream-oil-deregulation.pdf.