N.B. – This was published in Eye on Ethics: Asia Media Forum (September 8, 2008), the full text of which may also be retrieved from http://www.eyeonethics.org/2008/09/08/media-repression-and-the-journalist’s-ethical-dilemma/.

As a rule, journalists cover an event or issue as independent observers. They are taught not to have any direct participation in it because doing so could compromise their objectivity and credibility.

But this situation applies in a “normal” society. That the Philippine media sometimes face ethical dilemmas in fulfilling this “simple” rule indicates either one of two things – that journalists do not have a firm grasp of ethics, or Philippine society is far from “normal.” Of course, one can argue that it could be both.

In any case, the impartial manner of reportage expected of journalists is not as simple as it seems especially when they face interests that conflict with their own. Then again, reporters who remember their basic journalism ethics would know that they should inhibit themselves from reporting or commenting on issues and concerns that directly affect them.

Aside from being an ethical issue, the imperative of a journalist’s inhibiting himself or herself in times of conflict of interest also has legal considerations: Any charge of libel against him or her would most likely result in conviction, considering that the hard-to-prove element of malicious intent could be established once conflict of interest becomes apparent.

Media repression?

However, one may ask: What if the issue is about media repression? A journalist’s decision not to write about it due to conflict of interest would deprive the people of relevant information about the state of basic freedoms, of which press freedom is a vital part.

Covering issues related to media repression becomes even more complicated when journalists themselves do not just write about them but also take action against the Philippine government, which the Bangkok-based Southeast Asian Press Alliance (SEAPA) described as “hostile” in terms of protection of press freedom. In its study Slipping and Sliding: The State of the Press in Southeast Asia (May 2008), SEAPA observed: “The impunity that continues in attacks against Filipino journalists in 2007 was further complicated by the active promulgation of repressive laws and the restrictive interpretation of existing ones by the [administration] of President Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo.”

Covering issues related to media repression becomes even more complicated when journalists themselves do not just write about them but also take action against the Philippine government, which the Bangkok-based Southeast Asian Press Alliance (SEAPA) described as “hostile” in terms of protection of press freedom. In its study Slipping and Sliding: The State of the Press in Southeast Asia (May 2008), SEAPA observed: “The impunity that continues in attacks against Filipino journalists in 2007 was further complicated by the active promulgation of repressive laws and the restrictive interpretation of existing ones by the [administration] of President Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo.”

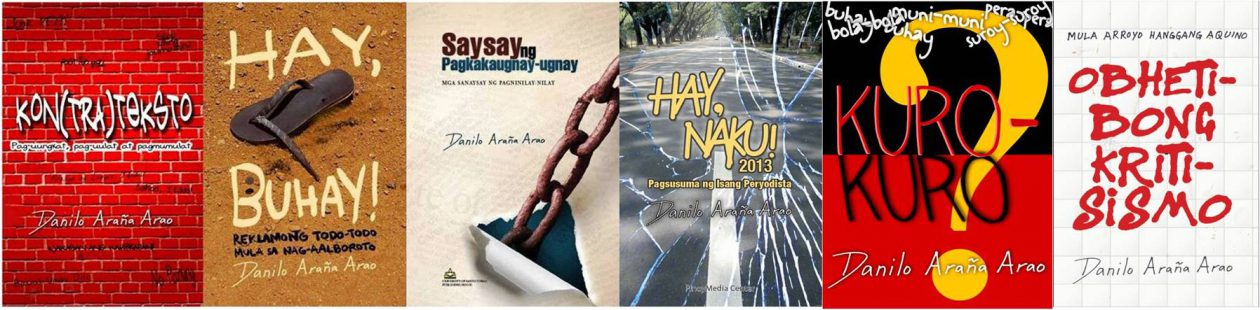

Danilo A. Arao (right) at the rally of journalists on August 16, 2004

in front of Camp Crame, Quezon City.

In the middle is Delfin Mallari, Jr. of the Philippine Daily Inquirer

who, years later, was almost killed in an ambush.

The dilemma can be better illustrated by this question from a reporter: “Are you here to cover or to join in the protest action?”

“Both,” I replied.

The date was August 16, 2004. The National Union of Journalists of the Philippines (NUJP) organized a morning rally to denounce the unabated killing of journalists. Together with about 100 journalists and journalism students, I walked from a building nearby to Philippine National Police headquarters at Camp Crame. To better catch the attention of passers-by and commuters on their way to work, we had a “die-in” (i.e., we lay on the ground with our fists clenched) prior to entering the gates of Camp Crame for a meeting with the police.

Photographers and camera persons expectedly covered what happened, especially the die-in, but joined the protest after they had taken their photos. In explaining their decision to both participate and cover the event, the journalists who were there said that they were all in it together, and that they should all seek justice for their slain colleagues.

Years later, the issue of media repression did not just include the killing of journalists but also some policies of the Macapagal-Arroyo administration. When Proclamation No. 1017 was imposed in February 2006, for instance, journalists immediately took the issue to the Court of Appeals (CA) as a result of the harassment and intimidation they experienced when the country was placed under the state of national emergency.

(The reader should know that I was a signatory to the CA petition and that a radio program I co-hosted at that time, Ngayon Na, Bayan [Right now, countrymen]! on DZRJ AM, was cancelled about an hour after the declaration of the state of national emergency and a few hours before I was supposed to go on board.)

Two suits filed

In January 2008, journalists filed not one but two cases – one with the Makati Regional Trial Court (RTC), the other with the Supreme Court (SC) – against the government for the arrest of more than 50 journalists who were covering the siege at the Manila Peninsula in November 2007. In the Makati RTC civil case (of which I was a signatory), journalists said, “The warrantless and oppressive arrest of journalists who were only peacefully exercising their constitutional rights clearly violates their right to a free press and project a `chilling effect’ on such freedom protected by the fundamental law of the land.”

Even if there were signatories like me who were not there at the Manila Peninsula when the arrests happened, it was argued that “as practicing journalists and advocates of press freedom and the right to information of the public on matters that concern their interest, [they] face the continuing threat of arrest and prosecution while in the exercise of their professional duty.”

The not-so-welcome news for journalists as regards this case came in June 2008: Having found no “sufficient cause of action for damages…that warrants further prosecution of the…case,” Makati RTC Judge Reynaldo Laigo dismissed it. In his decision, he said that the right of the plaintiffs as members of the press “was not violated or trampled upon by the respective acts of the defendants complained of.” He even added that the journalists were “so lucky” that they were not charged criminally for disobeying the police order to leave the hotel premises. “Thus their…having been handcuffed and brought to Camp Bagong Diwa, Bicutan, Taguig City for investigation and released thereafter was justified, it being in accord with the police procedure.”

In the fight against media repression, journalists in the Philippines are currently faced with two choices – be an active participant or maintain their “independence” by covering related issues and concerns as disinterested parties. Of course, one may argue if being a “disinterested party” in this issue is at all possible for journalists, even those who may not be affected by specific events like what happened at the Manila Peninsula on that fateful day of November 29, 2007.

In the final analysis, the journalists’ current ethical dilemma of directly participating in the promotion and upholding of press freedom is reminiscent of the dark days of martial law which was, ironically, a shining moment for those who had struggled to keep the torch of press freedom burning, dire consequences notwithstanding.

Mr. Arao teaches several Journalism, Media and Communication courses at the University of the Philippines College of Mass Communication (UP CMC), one of which is the master’s level course Media 230 (Media Ethics).