N.B. – This was published in the July-August 2009 issue of PJR (Philippine Journalism Review) Reports (pp. 17-18). The PDF file of this 28-page issue may be retrieved from http://www.cmfr-phil.org/wp-content/uploads/2009/08/PJR_Reports_July_-_August_2009.pdf.

The ghost of the political past has risen in the present. The specter of things to come is manifest in parallelisms with things that were.

The ghost of the political past has risen in the present. The specter of things to come is manifest in parallelisms with things that were.

Fourteen years of martial law rule in the Philippines prompt concerned Filipinos to periodically remind their fellow citizens of the dictatorial tendencies of those who assumed power after the ouster of the late Ferdinand Marcos in 1986.

Putting the country in a state of national emergency through Presidential Proclamation 1017 in February 2006 was the closest the country has come so far to the reimposition of martial law, even if PP 1017 was in effect for only a week. Ironically it happened as the nation was marking the 20th anniversary of the ouster of Marcos through the EDSA 1 in 1986, and that it was imposed by Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo, a beneficiary of EDSA 2, which ousted former President Joseph Estrada in 2001 and put Arroyo in Malacañang.

Arroyo is herself under threat of ouster for the same reasons that Marcos and Estrada earned the people’s ire – for human rights violations, electoral fraud, cronyism and corruption, among others. The June 19-22 survey of the Social Weather Stations (SWS) showed that her satisfaction rating is at -31 percent. The SWS added that 70% of respondents oppose changing the Constitution to allow Arroyo to remain as President beyond the expiration of her term in 2010.

“Saving” the republic

Marcos cited two main reasons for the declaration of Martial Law in September 1972 – to save the republic from communism and to create a new society. The Arroyo administration has raised the same communist bogey to justify the suppression of those who oppose it, whether from the political opposition, the mass movement, or various Leftist formations from party-list organizations to the Communist Party of the Philippines (CPP). “New politics” has also been promoted by the Arroyo administration in behalf of national development.

It was the new society then, it’s the new politics now. Both are nothing but empty rhetoric, but what’s significant is that the social change both regimes promise remains unrealized.

But Marcos and Arroyo have something more in common: they are two of the most unpopular Presidents the country has ever had. Understandable that most Filipinos have a sense of déjà vu in Marcos’s justification for the declaration of Martial Law in the late 1960s and early 1970s, and circumstances that the Arroyo regime is orchestrating and taking advantage of today.

Calls for the ouster of Marcos precluded authoritarian rule. As in the case of Arroyo, Marcos was accused of corruption. Both were said to be involved in various scandals where either they directly, their family members, or their close friends allegedly enriched themselves at the expense of the people.

A critical press

As far as the press and the media are concerned, the years leading to Martial Law had something in common with the present. In her book The Manipulated Press, Rosalinda Pineda-Ofreneo noted that in the early 1970s, “a large section of the Manila press sustained a strongly critical stance against the administration,” citing as an example the Manila Times’ opposition to Marcos, his policies and his actions “as early as the 1969 elections.”

Ofreneo also points out that the Lopez-owned Manila Chronicle (which used to be pro-Marcos because Fernando Lopez served as vice-president) became critical of the administration when the vice-president had a falling out with Marcos and resigned as secretary of Agriculture and Natural Resources in January 1971.

Reminiscent of Arroyo’s conflict with the Lopezes, Marcos had accused the latter of “fomenting unrest through their media.” With regard to the magazine Asia-Philippines Leader established in the 1970s, Ofreneo suggested that it had a political agenda, since Joselito Jacinto was its publisher, and he happened to be the “scion of the wealthy (Jacinto) clan embroiled in a bitter battle with Marcos over the Iligan Integrated Steel Mills.”

Intra-elite conflicts–plus

Such anecdotal evidence shows that the press’ opposition to the Marcoses was expressive of conflicts within various wings of the economic and political elite. But that does not mean that the opposition was solely limited to the defense of their narrow interests.

Campus publications like Lagablab (Philippine Science High School), the Philippine Collegian (University of the Philippines) and Pandayan (Ateneo de Manila University) had as editors and staff activists from their respective schools who consequently made their campus publications venues of dissent.

Other progressive organizations had their respective publications, as in the case of Kabataang Makabayan (National Youth) that published Kalayaan (which was also the name of the Katipunan’s publication, the lone issue of which had called for the overthrow of Spanish rule in the country). Underground publications like Ang Bayan of the CPP were also publishing even before the imposition of Martial Law.

The Philippine press today maintains the same critical attitude towards the Arroyo administration. In its own assessment last July 24, the University of the Philippines College of Mass Communication (UP CMC) said that the hostile environment the Arroyo administration has created is “unprecedented since the Marcos period,” and that it “has undermined the constitutionally protected freedom of expression in general and press freedom in particular.”

Just like the Marcos regime before the imposition of Martial Law, the current regime professes a commitment to press freedom that time and its actions have proven to be nothing but lip service.

“The imprisonment of Davao broadcaster Alex Adonis as a result of a libel case filed against him by the Speaker of the House of Representatives,” said UP CMC, “shows how government officials can use the law to silence and intimidate those who are critical of the powers-that-be. Broadcast journalist Cheche Lazaro was sued for wiretapping by a government official as a result of her work in exposing corruption. Journalists who went to Maguindanao were briefly detained when they covered the conflict there. All are the result of an atmosphere the Arroyo administration has created which encourages media repression.”

Same tactics

The same situation was apparent in the pre-Martial Law era. According to Ofreneo, “the Marcos administration did not take the attacks against it without hitting back.” Marcos’ tactics antedated those of Arroyo’s husband Jose Miguel “Mike” Arroyo. In July 1971, Marcos filed a P50-million libel suit against Time magazine, a “warning to local publications which would continue to subject his office and his person to `licentious assault.’” In addition, Sen. Benigno Aquino and the Manila Times Publishing Corporation faced a P5-million civil libel suit in November 1971.

Just as today’s concerned journalists and media groups have organized themselves to fight back by, among others, filing cases against Mike Arroyo for the latter’s libel cases against journalists and the Philippine National Police (PNP) and other government officials for the mass arrests of journalists covering the Manila Peninsula siege in 2007, Ofreneo observes that activist politics had “entered the confines of the (pre-1972) National Press Club (NPC) during the presidency of Antonio Zumel” who later on became chair of the underground National Democratic Front of the Philippines (NDFP). The NPC also provided legal and moral assistance to activists arrested for putting up the Dumaguete Times which Ofreneo says was “the first socially aware newspaper…which felt a deep sense of compassion with the people suffering from social injustices.”

Small comfort

The perception of Marcos and Arroyo towards the press are uncannily similar. Marcos, according to Ofreneo, believed that “the press had been infiltrated by the communists and attacked the `media oligarchs’ who had subjected him and his wife to `scandalous abuse and slander’ to topple down his administration.”

As the UP CMC’s statement said, Arroyo has also tagged critical media groups and at least one journalist “as enemies of the state either by the military’s infamous `Knowing the Enemy’ presentation or its 2007 Order of Battle in Davao.” In addition, Arroyo used every opportunity to dismiss serious accusations against her and her allies as simply being the work of “destabilizers.”

Today’s political opposition has stressed time and again that the reimposition of martial law is a distinct possibility due to striking similarities in the social and political circumstances then and now, while the Macapagal-Arroyo administration always dismisses such claims as unfounded. But for those who have survived Martial Law would recall, Marcos too denied any plans to impose it, as well as to prolong his rule.

The bombings that have been happening in the recent months are in this context convenient excuses for the declaration of Martial Law. The limitations provided by the 1987 Constitution on its imposition provide no comfort to people who are fully aware that the powers-that-be are planning to change the Constitution mainly to change the form of government and to lift term limits.

Notwithstanding occasional weaknesses in its coverage of issues, there is hope that today’s press can live up to the challenge of at least making the public aware of the volatile political situation through its critical stance towards an administration hostile to press freedom and its decision to resist all forms of media repression.

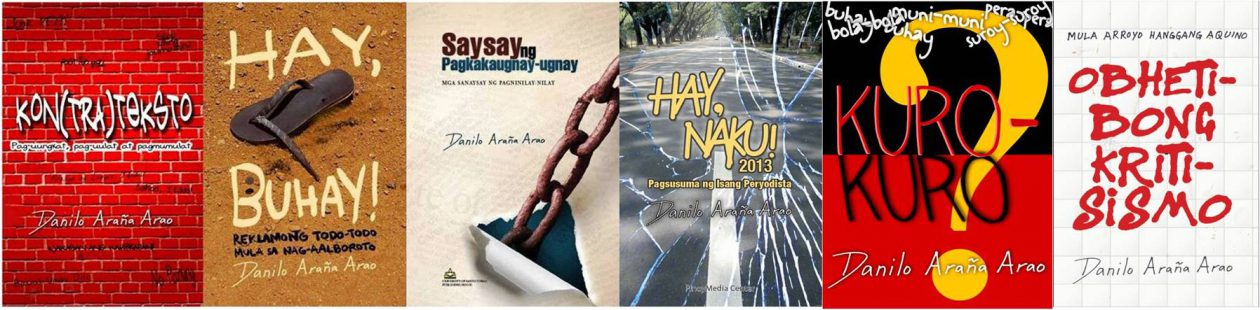

Danilo A. Arao is an assistant professor of journalism at the University of the Philippines (UP) Diliman. He is currently on special detail as a visiting professor at Hannam University’s Linton Global College in Daejeon, South Korea.