As of February 25, 1:38 a.m., 130 journalists already signed the unified statement against the right of reply bill sponsored by Sen. Aquilino Pimentel (Senate Bill No. 2150) and Rep. Monico Puentevella (House Bill No. 3306).

I was among the signatories to the statement (i.e., #40) because the points it raised had been articulated by concerned media groups and journalists like me a long time ago.

As early as November 23, 2005 when I was still chair of the University of the Philippines Department of Journalism, I attended a hearing of the Senate Committee on Public Information and Mass Media to put on record my opposition to the right of reply bill. In my position paper, I wrote the following points:

As early as November 23, 2005 when I was still chair of the University of the Philippines Department of Journalism, I attended a hearing of the Senate Committee on Public Information and Mass Media to put on record my opposition to the right of reply bill. In my position paper, I wrote the following points:

The bill’s objective to compel media organizations to publish or air replies of aggrieved parties is impossible to implement…The proponent’s [referring to Sen. Aquilino Pimentel] concern for those who are victimized by unfair media coverage is being addressed by various self-regulatory mechanisms like the Philippine Press Council (PPC), the ethics body of the Philippine Press Institute (PPI). Founded by the PPI in 1993, the PPC can compel a newspaper to print a rebuttal. If the concerned newspaper refuses to do so, other member-publications can print the reply.

As it is, the bill has negative repercussions on the workings of the press. Editors, normally referred to as the gatekeepers of information, should be allowed to choose which stories get published, aired or uploaded and which stories are given due prominence based on the time-tested elements of news.

Instead of coming up with bills that seek to legislate how the media should function, it would do well for legislators to help strengthen self-regulation in media by creating an environment conducive for the effective practice of the media profession.

At the UP Third World Studies Center Policy Dialogue Series on December 3, 2007 (or two years after I opposed the bill in the Senate), the right of reply bill was discussed in passing during the open forum. Among the points I raised are the following:

Everybody has the right to reply and they should be accorded with the necessary opportunity to have their letter to the editor or whatever statements they have, aired or uploaded in the case of on-line publication. Our main point of contention is that we cannot provide equal time or equal space to the so-called aggrieved parties because you will end up imposing objectivity. It is very much like the Code of Ethics. You do not have to legislate it. We are for self-regulation in media.

You may read the full text of the unified statement and the list of signatories after the jump.

Unified Statement on Right of Reply Bill

The Right of Reply Bill is an ill-conceived piece of legislation that violates two of the most cherished freedoms guaranteed by the Constitution, those of the press and of expression.

It is both unfortunate and ironic that the principal authors of the bill in the two chambers of Congress ought to have known better, Senator Aquilino Pimentel Jr. having earned his reputation as a champion of civil rights and Bacolod Representative Monico Puentevella having been president of the Negros Press Club.

It is also clear, from the pronouncements of both lawmakers, that this bill is a product of the sorriest excuse for legislation – personal pique.

The House version of the bill, HB 3306, parrots the Senate’s SB 2150 except it would have the reply run a day after receipt instead of the three days the Senate grants, and seeks to impose heftier fines and the absence of self-regulation (in the case of block-timers) and sunset clauses.

Both bills state that “all persons…who are accused directly or indirectly of committing, having committed or intending to commit any crime or offense defined by law, or are criticized by innuendo, suggestion or rumor for any lapse in behavior in public or private life shall have the right to reply to charges or criticisms published or printed in newspapers, magazines, newsletters or publications circulated commercially or for free, or aired or broadcast over radio, television, websites, or through any electronic devices.”

They also would mandate that these replies be “published or broadcast in the same space of the newspapers, magazine, newsletter or publication, or aired over the same program on radio, television, website or through any electronic device.”

The danger in the right of reply bill is that it would legislate what the media OUGHT to publish or air, while casting a chilling effect that could dissuade the more timorous from publishing or airing what they SHOULD.

The bills would free public officials, especially the corrupt – and they are legion – of accountability and give them carte blanche to force their lies on the suffering public.

As one article on the right of reply bill says, “It lumps together imputations of a crime with simple criticism ‘of any lapse in behavior in public or private life’ or what would otherwise be considered ‘fair comment.’ There is no judicial review. It does not differentiate direct and indirect criticism. It has been noted that under the proposed law a journalist does not even have to be in error to draw a right of reply claim.”

We would be the last to say that the Philippine media are without fault. Yes, we understand perfectly the frustration and anger of Pimentel and Puentevella over some media outlet’s refusal to air their sides on issues.

Alas, but we cannot allow the sins of the few to be an excuse for the wholesale muzzling of a free press and the suppression of free expression. To do so would to allow bad governance to triumph.

We call on Senator Pimentel and Representative Puentevella to withdraw their bills.

We urge the media and the people to close ranks against the passage of this bill, to challenge it before the Supreme Court if it is passed, and, if even that fails, to defy it by refusing to comply.

No less than our freedoms are at stake. This is a battle we cannot afford to lose.

Signed by: (as of Feb 25, 2009, 1:38 am)

- Nestor Burgos, Philippine Daily Inquirer

- Nonoy Espina, inquirer.net

- Sonny Fernandez, ABS-CBN

- Rowena Paraan, Philippine Center for Investigative Journalism

- Alwyn Alburo, GMA Network

- Marlon Ramos, Philippine Daily Inquirer

- Dani Lucas, ABS CBN

- Ilang-Ilang Quijano, Pinoy Weekly

- May Rodriguez, Freelance

- Julie Alipala, Philippine Daily Inquirer

- Cheryll Fiel, davaotoday.com

- Jun Godoy, DXOC-Ozamis City

- Arnell Ozaeta, Philippine Star, DZMM

- John Heredia, Filvision Alto Cable-Capiz

- Desiree Caluza, Philippine Daily Inquirer

- Dabet Panelo, NUJP

- Miriam Grace Go, Newsbreak

- Sarah Katrina Maramag, College Editors Guild of the Philippines

- Maurice Malanes, Philippine Daily Inquirer

- Jofelle Tesorio, ANN

- Allen V. Estabillo, MindaNews

- Jun Lopez, Malaya

- Gerry Albert Corpuz, Bulatlat.com and United Press International (UPI) Asia Online

- Delfin T. Mallari Jr. Philippine Daily Inquirer

- Arlyn dela Cruz, NET-25/ Philippine Daily Inquirer

- Rorie Fajardo, Philippine Human Rights Reporting Project

- Ronalyn V. Olea, Bulatlat.com

- Jun Ariolo N. Aguirre, Hala Birada News Weekly

- Rey Tamayo, Jr., Good News Services

- Alexander Martin Remollino, Bulatlat.com

- Vijae Alquisola, College Editors Guild of the Philippines

- Elmer James Bandol, cbcpnews.com

- Ansbert Joaquin, Philippine Daily Inquirer

- Kathleen T. Okubo, Northern Media Information Network

- Dino Balabo, Philippine Star, Pilipino Star Ngayon, Mabuhay, CLBW

- Inday Espina-Varona, Philippine Graphic

- Susan N Palmes- Mindanao Gold Star, Cagayan de Oro

- Malu Cadelina Manar, Notre Dame Broadcasting Corporation, Kidapawan City

- Rizaldy Jose GMA-Network

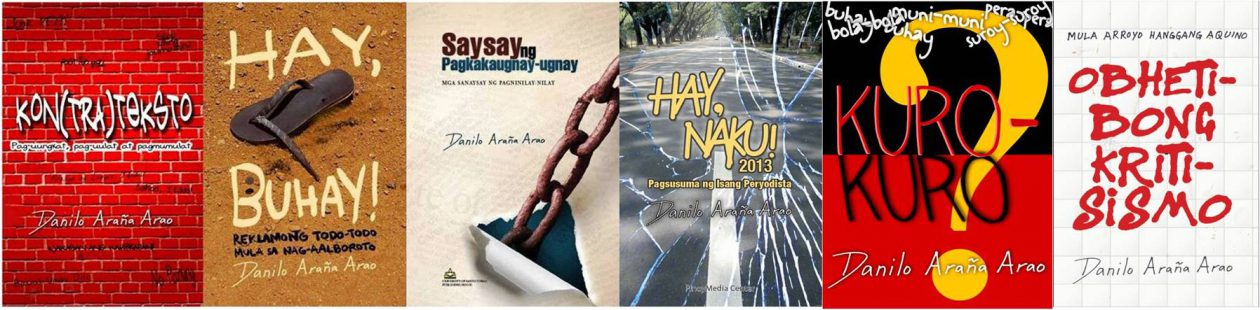

- Danilo Arao, Bulatlat.com, Pinoy Weekly

- Rey Tamayo, Jr., Magandang Balita

- Joey Aguilar, Punto Central Luzon/gmanews.tv

- Marlon Alexander Luistro, GMA 7

- Danny Estacio, Balita

- Jason Vallecer, Eyewatch

- Olan Mape, Manila Star/ LD Chronicles

- Bert Abrigo, GMANews.tv

- Francia Malabanan, GMANews.Tv

- Ryan D. Rosauro, NUJP-Ozamis City

- Ire Jo V.C. Laurente, Journal Group-Mindoro

- Frencie L. Carreon, The PhilSouth Angle

- Ederic Eder, Tinig.com

- Reil Briones- Bandilyo/ Kiss FM

- Candace T. Giron, Freelance Journalist

- Maricar Cinco, PDI

- Nanette L. Guadalquiver, The Visayan Daily Star, BusinessWorld

- Renz Belda DZRH/ DWAW Batangas

- Angel Ayala, Bicol Media/Radio Natin Sorsogon/NUJP Sorsogon

- Dodong Solis, RMN/DXDC Davao

- Lalaine Marcos Jimenea, Eastern Visayas Mail and Eastern Samar Reporter

- Joyce Panares, Manila Standard Today

- Abigail T. Bengwayan, Northern Dispatch

- Cesar S. Ramirez,The Philippine STAR

- Genivi Factao, Business Insight (Malaya)

- Trina Federis, College Editors Guild of the Philippines

- Thony Arcenal – PolicefilesTonite, DZME1530Khz, CLMA

- Voltaire Domingo, NPPA Images – Manila

- P.James M. Tremedal, www.mpilgrim.tk / www.pag-enews.tk

- Sonia M. Capio, DWNE 900 kHz

- Joey E. Tamunda, GV-AM 792Khz, Balitalakayan – Central Luzon

- Mark Anthony N. Manuel, Manila Bulletin

- Edwin G. Espejo, Freelance Journalist

- Jess Malabanan, CL Daily/Bandera/Reuters/abs-cbn.com

- Jinky Jorgio, Freelance Journalist/local coordinator BBC

- Tonette T. Orejas, PDI correspondent

- Ariel D. Borlongan, Bigwas, Jaryo Alisto

- Elina M. Velasco-Ramo, Northern Dispatch

- El Interino, bulatlat.com/asianpress.net

- Darwin Wally T. Wee, NUJP ZamBaSulTa chapter, BusinessWorld

- Hazel S. Alvarez, ABS CBN-Bacolod

- Butch Gunio, Central Luzon Business Week

- Arturo Boquiren, Northern Dispatch Weekly and The Weekly Junction

- Aquiles Z. Zonio/PDI Correspondent (Socsargen)

- International Federation of Journalists-Asia Pacific Alliance, A Journalists Association in Australia

- Ma. Cecilia Rodriguez, Correspondent, Philippine Daily Inquirer

- Federico D. Pascual Jr., Philippine Star, ManilaMail.com

- Vergel Santos, Business World

- Joe Pavia, Philippine Press Institute

- Luis Teodoro, Center for Media Freedom and Responsibility

- Jessica Soho, GMA News and Public Affairs

- Howie Severino, GMA News and Public Affairs

- Ed Lingao, ABC TV-5

- Charie Villa, ABS CBN News

- Isagani Yambot, Philippine Daily Inquirer

- Sandra Aguinaldo, GMA Network

- Mark Merueñas, gmanews.tv

- Billy Begas, Bandera

- Antonio Gabriel, ABC TV-5

- Ramir Padua

- Manuel Tupas

- Danny Santos, Sunshine Radio DZAR

- Erika Tapalla, inquirer.net

- Sherrie Ann Torres, ABC TV-5

- Amor Barbo Docado, ABS CBN Global

- Ferlina Mungcal, ABS CBN Global

- Roy Gersalia, PDI, Sorsogon Newsweek

- Artemio Dumlao, Philippine Star

- Ruben Alabastro, Philippine Daily Inquirer

- Tony Bergonia, Philippine Daily Inquirer

- Leti Boniol, Philippine Daily Inquirer

- Sandra P. Sesdoyro, Philippine Daily Inquirer

- Richard R. Gappi, NUJP-Rizal

- M.A. Kit Bagaipo, PDI, Bohol Chronicle, dyRD-AM

- Francis Allan L. Angelo, The Daily Guardian (Iloilo)

- Raffy Beltran, ABS CBN Global

- Jeffrey M. Tupas, Philippine Daily Inquirer

- Germelina Lacorte, Correspondent, Philippine Daily Inquirer

- Rene Acosta, Business Mirror

- David Santos ABS-CBN Zamboanga

- Raffy Jimenez, GMANEWS.TV

- Chris Panganiban, The Peninsula Qatar

- Germelina Lacorte, Philippine Daily Inquirer

- Boy Ryan Zabal, Aklan Police and Defense Press Corps

- Loloy Zuasola, Freelance Journalist

- Jojo Pasion Malig, MVIM Newslink Services

- Robert Gonzaga, Philippine Daily Inquirer

- Carla Gomez, Visayan Daily Star/ Philippine Daily Inquirer

- Rustico Otico, BusinessWorld

- Wilfredo Villareal, GV-AM 792, Luzon Banner, GMANEWS.TV

- Arlene Burgos, Bandera

Pimentel & Puentevella integrity is doubtful.

Reply: Why is their integrity doubtful? Hope you’ll find time to explain. Thank you.

Just a question and I beg your indulgence.

The Philippine Press Institute Journalist’s code of Ethics states:

“I shall scrupulously report and interpret the news, taking care not to suppress essential facts nor to distort the truth by omission or improper emphasis. I recognize the DUTY to air the other side and the DUTY to correct substantive errors promptly.”

and

“I shall refrain from writing reports which will adversely affect a private reputation unless the public interest justifies it. At the same time, I shall fight vigorously for public access to information, as provided for in the Constitution.”

However, we cannot deny that there are instances where stories are run without airing the other side and some times the private reputation of individuals are damaged without substantially proving that it would be best for the public interest.

What do we do then?

Normally, we have to resort to writing to the editor or producers of the TV or Radio program. Sometimes the letter is printed or aired, weeks or months after — some times with an additional comment from the editors or producers.

In cases where the media organization admits to having published or aired an erroneous report, the errata is often printed in a small box.

Or if the subject of the adverse reports has the resources and time to pursue a libel case, he or she files a case in court which can take months if not years.

In the meantime, the non-media person who was subject of an erroneous or adverse report has to suffer.

I think that the ‘Right to reply’ bill is merely a reaction to how some members of the media carry out their jobs.

The question is: How do we ensure better adherence to the Journalists’ Code of Ethics?

Reply: You raised very valid points which are the main causes of the media consumers’ frustration brought about by irresponsible reporting and the lack of ethics among some journalists. But is legislation the solution to the problem? Analyzing the contents of the Senate and House bills, one can easily conclude that an editorial nightmare will happen once media organizations are forced to comply.

In the final analysis, self-regulation is still the key to having a responsive and responsible media. There are conscious efforts on the part of journalists towards strengthening self-regulation, as in the case of numerous workshops conducted by various academic and media organizations.

Aggrieved parties are not totally powerless when it comes to abusive media. If they are media-savvy enough, they can help expose these media organizations through the latter’s competitors or even through media monitoring organizations like the CMFR.

I think better adherence to the prescribed code of ethics could be achieved by media consumers taking part in strengthening the media. Contrary to popular belief, self-regulation in media is not just the responsibility of journalists and other media workers, but also the audiences.

On the point of self-regulation.

Correct me if I am wrong and I really want to be enlightened on this point, how does media regulate itself?

Are you referring to media organizations such as the Inquirer which has an ombudsman? Or are you referring to bodies such as the KBP, the Philippine Press Institute or organizations such as the National Press Club?

Who acts as impartial arbiters? What is the process for seeking redress? What complaints can be acted upon and what cannot?

Take the case of KBP and GMA7:

On September 1 of the same year (2003), GMA Network withdrawn its membership from the Kapisanan ng mga Brodkasters ng Pilipinas (KBP),[7] after incidents involving host Rosanna Roces, alleged commercial overloading and interfering when news anchor Mike Enriquez aired his complaints over his radio program, Saksi sa Dobol B, against Lopez-owned cable firm SkyCable’s distortion of GMA’s signal on its system, and a lost videotape containing evidence that the cable firm had violated the rule on soliciting ads for cable TV. — source Wikipedia (because I am rushing, but I read about this years ago)

Now, granted that this is not what usually happens with self-regulation, it does point out a crucial flaw and that is, if you do not agree with the self-regulating body, all you have to do is bolt out.

Having been somewhat part of the media myself, I can say that even reporters policing their own ranks against ‘envelopmental journalism’ is perilous to their professional advancement.

At times, all it will amount to are ‘white papers’ circulated in newsrooms and press offices through fax.

At other times, a concerted effort will happen within a news organization and the target of the complaint may either be a supervisor or a fellow reporter. There are cases where the complaint is addressed satisfactorily and there are instances where the subject of the complaint (because of strong connections with the powers that be) survives the onslaught despite damning evidence. The survivor of the complaint, in one case, eventually was able to get a more influential position within the media organization and as could be expected, sought retribution on those who tried to get him fired.

I can go on and on, but my point is this:

We have to realize that media’s ability to regulate itself is flawed and unless we can address these flaws more effectively, there will be a clamor for a better means to keep media in check.

Reply: Self-regulation can be done at various levels and involves not just media organizations but also media audiences. Internally, media organizations can come up with its own reader’s advocate (in the case of the PDI) or news ombudsman whose primary responsibility is to ensure that complaints from audiences are properly addressed by the editors, reporters and other media workers concerned. Associations formed by media organizations and journalists can also be self-regulatory mechanisms, as is the case of the PPI and the KBP.

How does it work? From what I know, the Philippine Press Council (PPC) which is part of PPI is the one that hears complaints of readers of PPI’s member-publications. If a publication which is the subject of complaint refuses to publish an aggrieved party’s letter to the editor, the PPI can compel the other member-publications to publish the said letter. KBP also has its own Standards Authority which functions like the PPI’s PPC.

Just to cite an example, Art. 9, Sec. 3 of the KBP’s Broadcast Code of the Philippines (2007) states: “Persons, institutions or groups who are the subject of complaints, criticisms, or grievances aired on a station must be given the opportunity to reply immediately or at the earliest opportunity within the same program, if possible; if not, the opportunity to reply should be given in any other program in similar conditions.”

KBP classifies any violation of this provision as a “Grave Offense” and the penalties range from censure to 120-day (for a radio station) or 150-day (for a TV station) suspension of membership privileges, aside from fines ranging from P30,000-P60,000 (radio) to P40,000 to P70,000 (TV). For individuals who violate Art. 9, Sec. 3, the penalties, depending on the number of offenses made, are reprimand, 60- or 90-day on-air suspension and revocation of accreditation, aside from fines ranging from P15,000-P30,000 (radio) and P20,000-P35,000 (TV).

We should also keep in mind that some media organizations like the PDI, ABS-CBN, GMA 7 and Sun.Star have their own codes of ethics and consequently their own internal mechanisms for handling complaints.

I do agree that the system is not perfect and that the flaws are very apparent. For one, not ALL media organizations have internal mechanisms, and it’s not as if they are all members of the likes of PPI or KBP, as you correctly pointed out.

The solution to this problem is not government intervention through legislation of the workings of the press, as what the RORB seeks to do, but the strengthening of self-regulation to make sure that it is give the chance to work.

As a former media practitioner, I’m sure you’ll agree that media organizations have their work cut out for them in strengthening self-regulation, and that they need the support from the academe, media-related NGOs and concerned audiences.

The first two are already doing their share through training and media monitoring, among many others. What proves to be necessary at this point is to organize media advocacy groups composed of concerned audiences that can take media to task for their inadequacies in doing their work.

All in all, self-regulation can be strengthened by promoting media literacy not just among media organizations but also among media audiences.

Thank you for your comments and please keep them coming.

Sir Danny,

I can’t believe that Senator “Nene” Pimentel who suffered and witnessed the muzzling of the press during Marcos is now the author of the right of reply bill. People do change position after all when they become the power holder.

The bill which proposes equal space rebuttal would drastically shift the burden of resources and hardships on the press people which is unfortunately already under threat. While this is different from Marcos shutting down the press, the bill ultimately cut the the effectiveness of the press to serve the public to expose corruptions and abuses of public officials because it has to place the fried chicken of lies packaged under right of reply bill on the same plate. The politicians are having the field day of their lives.

The press is facing its grievous threat under the guise of equal space for lies.

Reply: Thanks for your comment. When I met with Sen. Pimentel at a public hearing in 2005 about the RORB, he said that when he was still mayor of Cagayan de Oro he was consistently attacked by the community press there and that his replies were often never published. He had an altruistic tone that what he is doing is to protect the powerless from irresponsible reportage.

Together with representatives from other media organizations, we raised the editorial nightmare that will be brought about by forced compliance on any right of reply law.

Somehow, the RORB got archived then but it is now being resurrected with some revisions like the sunset clause which states that it will take effect for only seven years.

Minor side issue that must be answered: Why should a right of reply law have a “shelf life” if it is really meant to put media in check? Or is this just simply a case of a “seven-year itch?”

Sir, may I add, in researching a possible solution to this regulation/self-regulation issue a friend and co-worker pointed me to the UK’s Press Complaints Commission.

Can you tell me about your views on having such a Commission here in the Philippines?

Here’s the URL of their website: http://www.pcc.org.uk/about/whatispcc.html

Reply: Thanks for sharing the link to our readers.

The functions of the UK PCC are actually being done by institutions like the PPI and KBP, though they both apply only to their respective member-organizations.

Aside from monitoring the contents of journalistic outputs, the CMFR also hears complaints from media audiences and conducts its own investigation. Its findings are normally published in its publication called PJR Reports. The workshops conducted by CMFR (where I sometimes get invited as resource person) aim to help journalists adhere to the highest professional and ethical standards.

Unlike the UK PCC which is confined to newspapers and magazines, CMFR’s mandate is multimedia in character. Nevertheless, there are a lot of lessons to be drawn from the rich experience of the UK PCC, especially when it comes to motivating audiences to put on record their complaints.

Sir Danny,

Thank you for your time. Indeed, the Senator may have the good intention. But that is part of being a public official and vehicle for good governance. A strong democracy needed the press and public critics to scrutinize wasteful spending of the government paid by taxpayers’ money. Penalizing the press for every infraction is like putting a gun to ones pocket especially for the low income community press. Instead, the RORB (1) gives more power to already powerful politicians and public officials, (2) criminalizes an an act not sanctioned in western countries, and (3) legitimizes economic hardships on the press for every infraction, thereby (4) weakening the press institution (necessary for a strong democratic process) as a whole.

In “protect the powerless”, the dear Senator should re-examine what was the press is all about. Government officials are cloaked with the power of the state and the only known avenue for the governed and the paying public is the press.

You are right, if it is temporary then it serves only a special interest.

Reply: Indeed, the real challenge is how to strengthen self-regulation in media and how to make it work. Legislation does not solve the problems of the press. All the best!

Danny,

Thank you for taking time to respond. As a former media practitioner, I welcome the chance to learn more about journalism and the rules (not suggestions) that apply to the profession. I think you really defended self-regulation very well and this really helps a lot of people to understand the issue better.

One point that was brought up by a reporter is that the media needs as much leeway as possible especially at this time in order to become more effective in exposing the acts of corruption in government. If the RORB were in place, perhaps news media organizations would not be able to print or air stories against government unless the officials or agencies gave their side. All that would be needed to shut the media up would be a refusal to air their side.

Perhaps, along with a RORB, the news media should be given equal arms in the form of a stronger FOIA or a Right to Demand Answers Bill. ;-)

Under my proposed legislation, government officials and agencies will be deemed to have given their consent to news media to run a story without their side if they do not answer calls or questions from the media. The proposed legislation would make it illegal to say ‘no comment’ on matters concerning public interest.

What say you?

Take, for instance, the bribery allegations at the Department of Justice

Reply: That’s a suggestion worth deeply studying and it doesn’t deserve a knee-jerk response from a fellow journalist like me. But here’s my two cents nevertheless: An advantage of your proposed legislation is that government officials will be pressured to be more transparent on public interest issues. Then again, one may argue why “consent” is necessary from sources in running stories they don’t want to comment about? This will definitely compromise press freedom if consent from sources (even if government officials) becomes a requirement in publishing, airing or uploading stories. I think the challenge is not how to “effectively legislate” the workings of the press but how to “effectively create” an atmosphere that is conducive to stronger self-regulation in the media.

Please feel free to rebut the arguments I raised. I have to confess that this is just a quick reaction or reflection in the middle of editing and some administrative tasks. All the best!

sana masolve na ito

Sagot: Oo nga. Ang tanong, kailan at sa paanong paraan?

Hi Sir Danny,

To be honest, I found myself reluctant to post this comment (since I am not a media practicioner, but I was part of a publications org back in college and have finished AB Communication), but nonetheless I’d like to share some thoughts from the top of my head:

I understand your concern when you mentioned that implementation of the RORB may result in an editorial nightmare. But I also recognize the need for such legislation as some media channels and bodies have become very abusive of their existing rights (to be honest, I do not watch ABS-CBN anymore owing to my disgust on how they produce news segments; sometimes the most quantitative reports manage to get loaded with unsolicited opinions and biases; other networks still have subtle biases and/or promotional insertions that find themselves in news shows production).

If I may comment as well on Sir Paul’s suggestion (Right to Demand Answers), I don’t think this Bill will be any better than the RORB; in fact, it may make matters worse. A Right to Demand Answers can easily be abused (my apologies for the next part, as I am sure some people may react), since we Filipinos are infamous for taking the “Pilosopo” approach. Demanding answers is one thing, but asking the right questions is another. We all hate how some lawyers question during a hearing (in this scenario, witnesses on the stand are compelled by law to answer any question thrown at them by lawyers); so what makes media questioning any different once a right to demand answers is passed? At least with a RORB, the replying party may choose to waive their right to answer awry questions.

My point is that existing media regulations should be more visible, so as not to have non-media practicing citizens like myself agree to such legislation. Everyone needs to see justice – crime begets punishment. Without this people lose hope, and this leads to despair. I’ve honestly given up hope in local news broadcasting programs a long time ago; almost a decade has passed and it hasn’t won me back.

Media regulation is a must, and if it takes such a legislation to be the avenue, so be it. I hope I am proven wrong not only by you, Sir Danny, but by what I see whenever I switch on the television or radio.

Just one suggestion to the legislators: increase the fine; 70,000 pesos is loose change for huge broadcasting networks.

Thanks so much Sir Danny, and I sincerely hope I have not offended anyone with this comment!

Reply: I appreciate your comments and I doubt if there is anyone offended by them. Your frustration is very understandable, and I fully agree that mainstream media organizations tend to shortchange audiences when it comes to shaping public opinion.

Media regulation is indeed a must, and we have no quarrel with that. But there is a difference between regulation that is imposed by the powers-that-be (in this case Congress) and regulation that is conducted through self-policing mechanisms in the media. Do we trust the media enough to police themselves? I am sure you don’t as I admit that not all journalists live up to the highest professional and ethical standards. But please consider that there are still some (even a few) who are still worth emulating. It may be a very tedious and frustrating process, but self-regulation is the only way to ensure that press freedom will not be compromised and coopted by those in power.

The danger in legislating the “right of reply” is that the media-savvy elite can control media content by compelling media organizations to publish whatever replies they have, no matter how mundane they may be. Important issues that must be made known to the public will end up competing for space with such mundane replies, with the latter being given priority due to legislative imposition.

A fact that is often overlooked in self-regulation is that it cannot work well without the support of critical media audiences. There is a need for the people, preferably as an organized group, to take media to task for its failure to provide relevant information. For as long as there are concerned citizens like you who can and will not stand idly by as media continue with their nefarious ways, there is always hope for self-regulation in media. I wish you the best and thank you for your comment.

Hi Sir Danny,

Thank you so much for your reply! This enlightenment will have me thinking about it, and rest assured I keep a neutral stance whenever dealing with the people in any informal group I interact with.

Is there any group that I or any concerned, non-media professional could join to lend a hand in these regulations? Although there are existing bodies, we cannot deny the fact (or at least the possibility, although I am leaning towards it being a “hidden fact”) that these organizations or institutions have insiders with vested interests (either personal or in association with a media body).

I’d suggest an idea, but I’m sure several people have already suggested it (or perhaps this is already in place, but I’m not really sure). In any case, here it is: why not put up an organization of concerned citizens who give constant feedback on news and public affairs items on any media channel? This group may not be consisted of known personalities; in fact, the officers could be replaced regularly (not just yearly, but more of quarterly or monthly; similar to a jury, along with its randomized yet strict selection process) with a quantified and standardized assessment or grading system. Representatives from different sectors should also be present. An existence of such an organization could be the solution to the problem which these legislators believe exists.

Please let me know your thoughts on this, and if you find it favorable I can assist you with the planning and implementation of such a program. Thanks so much sir!

Reply: Actually, the Media Literacy training program at UP has an objective of organizing media advocacy groups that would be focused on a consumer-oriented media monitoring. Its function is exactly what you had written: It will monitor media content and call the attention of media practitioners on certain errors in coverage. Right now, this is still a pipe dream, and it would be very welcome if you can help organize one. The culture of media monitoring is slowly being accepted by professional media organizations, though only a few organizations like the Center for Media Freedom and Responsibility (CMFR) and UP CMC do this. Even then, the monitoring is from the perspective of the professionals and academics. We should have monitoring coming from enlightened audiences like you. If you’re really serious about engaging in media monitoring, it would do well to coordinate with either CMFR and UP CMC. I would prefer to meet with you in person but I am in Korea right now and will not be back at UP until the first quarter of next year. But my other colleagues at CMFR and UP CMC can help you.

Thank you very much sir! I will draft a proposal for the program mechanics and will let you know as soon as I have the first draft ready.

I admire your very educated way of responding to comments. While I agree in a certain way that you are against censorship, I do not believe in moderation. Let the readers post anything they want, just reply SPAM. Then let the other readers decide if it is really spam by way of a thumbs up or thumbs down vote beside the comment. Isn’t that a better way of exercising freedom of speech? If one gets thumbs down 5 times, the system automatically deletes the comment. The system decides, not the moderator. That way, they will be discouraged from spamming if they are put down by their own peers.

It is quite frustrating to post a valid comment only to see that it never gets posted because the moderator is away or, much worse, biased. No wonder certain sectors are in favor of the RORB.

You said “We should also keep in mind that some media organizations like the PDI, ABS-CBN, GMA 7 and Sun.Star have their own codes of ethics and consequently their own internal mechanisms for handling complaints.” But the first two in particular don’t let comments get through. ABS-CBN doesn’t even allow one to comment directly at their program’s webpage. You are made to spend 2.50 to text your comments to santino. You believe that?

It’s true that there is a constraint on space and time for them to publish or air the reply. But considering that we have the WWW, why not allow the aggrieved parties to blast at them via the internet, sans moderation and without feigning server bogged down due to message overload! ABS-CBN will surely use that excuse.

The press or media in general is called the Fourth Estate. Very distinguishing, and they are damn proud of it. They serve as check and balance for the government and society. Question: Who will check and balance the media? They will do that by themselves? Through whatever channels you’ve pointed out, which are also controlled by their peers or colleagues? Is that genuinely possible? Dream on pards!!!

Allow me to introduce the genuine Fifth Estate… the Netizens. Forget the RORB. Let the public post comments freely and without moderation.

Reply: Thank you for your insights and I appreciate your taking time to write a very lengthy comment as regards censorship and moderation of comments in blogs.

While you did not state it explicitly, I think we both agree that there is a difference between censorship and moderation. The latter is part of the “gatekeeping” mechanism of media.

I believe that spam comments are among the reasons for the need to moderate comments. I have to admit that I am forced to moderate comments due to the sheer number of spam comments I get (more than 60,000 caught by Akismet so far).

Some blogs or websites require online users to register before posting comments, and this kind of moderation is understandable to ensure that anonymous postings will be minimized (though it is also possible that an online user can use a bogus identity in registering). Suffice it to say that there is no fool-proof way to get rid of spam messages, hence the need for moderation in whatever way possible.

I share your frustration with the irresponsibility of media to air the other side. But monitoring the media need not be done only by their colleagues, but also concerned citizens like you. What is sorely lacking in the Philippines is an organized consumer advocacy group whose mandate is to take media to task for whatever excesses they do. I think a high level of media literacy among audiences could also help a lot in making sure that the media would be reminded of their role in shaping public opinion.

Is there a guarantee that the media would listen? The answer is no. Then again, I’m sure you’ll agree that their credibility will greatly suffer once criticisms about them are made public, hopefully resulting in less audiences and, more importantly, reduced profits.

Yes, the online users are part of the audiences that should take media to task, though they should exercise responsibility in blogging and posting comments.

Going back to the issue of moderation, there are other reasons why it’s necessary aside from the preponderance of spam messages. In my case, for example, I sometimes edit typographical and grammatical errors of those posting comments here not only to spare them the embarassment but also not to muddle their intended message. There are also those who change their mind and request that I delete their comments. Some of the online visitors also make a mistake of posting the same comment twice. Such kinds of moderation, I think, are acceptable.

Just like you, I take issue, however, with bloggers and website owners who refuse to post valid comments. I wish you all the best!

Hats off to you! You’re the very first (I should say, only) person who actually replied to my comment, and quite promptly too.

If it’s anything to you, I will state explicitly that there is indeed a big difference between censorship and moderation. But, it is also a fact that most sites do censorship in the guise of moderation. ABS-CBN is on top of my list. They make you register online, ask you to wait 15 minutes for your password to be sent to your email account… It’s been a day since, I have yet to receive one. It’s not censorship anymore. More like sending you on a wild goose chase until you lose steam and eventually forget what you want to say or just simply give up.

“But monitoring the media need not be done only by their colleagues” I’d have to emphasize that it’s more appropriately SHOULD NOT. If you task a rival station to do the job as per provisions in their code or whatever they call it, it will only end up in mudslinging and away from the real issues. That’s how immature they really are.

I feel, it is the frustration of certain sectors that lead to their going with the RORB. Some of our media men act like spoiled brats with press freedom as their toy. As to the question whether media would listen to criticisms, the answer would be hell no. Profit and fame are their main concerns. Sensationalism (I’d have to say I hate this word) is the name of the game, and very often shot out of proportion.

Yes, I do agree that “their credibility would suffer…”, but the question is how to make it public when valid comments get moderated (ehem censored). Will they forego moderation in exchange for not passing RORB? I doubt. They’d want the best of both worlds.

… 2 cents worth of a market vendor from a remote place.

Cheers!!!

Reply: Regarding ABS-CBN’s practice (or malpractice) of taking forever to approve your registration to comment on its website, I wouldn’t call it censorship. At least not yet.

Even at the risk of speculation, maybe we can just attribute it to plain incompetence of the person or group in charge of the the network’s website. If you’re still patient enough, you can try sending an email to complain about the inconvenience you’ve had. If the media organization is sensitive to the needs of its audience, you should get a complaint, even if delayed.

As regards mechanisms to make public the moderated (or “censored”) comments, that’s where the entire cyberspace becomes useful. In much the same way that a webmaster or blogger has the option to block your valid comment, you have the freedom to post it in discussion groups, e-groups, other people’s blogs (like mine), and even your very own blog. If you do that, then the credibility of the erring media organization would suffer, assuming of course that audiences generally agree that your comment is indeed valid and not spam.

THIS IS THE WAY WE DO IT IN MAKATI (Ganito kami sa Makati). City cops collar one of the occupants of a tenement building for refusing to leave even after he and fellow residents received a notice to vacate from the local government which cited the need to renovate the building. http://inquirer.net/

Is this responsible? It’s obviously poking fun at Binay. They can do that because they are in the position to do that. They find it amusing. As an opposition to RORB, do you find it amusing?

My point is, they are paid or are making money out of poking fun at people. Let’s say Binay, out of broad-mindedness, chose to ignore this. They would still feel smug about their article. What if someone like me would choose to criticize the paper for this by sending a comment, would it be considered as spam? Would you personally view this as spam?

Spam is defined as unwanted e-mail (usually of a commercial nature sent out in bulk). A comment against what they posted would be unwanted, but definitely not commercial in nature and not in bulk. Nevertheless they would view it as spam because it’s unwanted, because it’s against what they want people to believe. Would you consider it as spam?

Reply: In my professional opinion, that is responsible commentary and the title in all caps shows wit on the part of the caption writer. Readers like you, however, cannot be blamed if you see it as poking fun at Binay. It is, after all, his slogan in extolling his achievements as mayor.

We have to remember that as a public official, his actions (and that of his subordinates, including the police in his area) are always under public scrutiny. Binay and others offended by such a report have the option to write a letter to the Inquirer. In case this does not get published, they can file a complaint with the Philippine Press Institute (PPI). The PPI, through its Philippine Press Council (PPC), can compel the Inquirer to publish the letter. If it refuses to do so, other PPI member-publications will publish the letter, putting the Inquirer in a bad light.

The point here is simple: There are existing self-regulatory mechanisms to check against abuses by the media. These are definitely not perfect, and some aspects actually need to be strengthened. Any legislation that would impose any right (e.g., RORB) or standard (e.g., objectivity, accuracy) will only be counter-productive to self-regulation and, in the final analysis, an editorial nightmare in terms of the media’s day-to-day operations.

As regards the question if forwarding this Inquirer report is considered spam, I cannot give a categorical answer as it depends on the situation and manner in which it is forwarded. Since we are discussing it in relation to RORB, it is not spam. But if you were to forward this article as a comment to an unrelated topic (e.g., VFA or agrarian reform), then it might be considered spam by virtue of its being off-topic (thus unwanted).

Pardon me, I’m not a journalist and I’m no literary genius either. I tend to jump the gun and misuse some terms. Yes, you’re right that it’s not censorship, it’s denying access which gives more merit to the cause of pro-RORB sectors.

I’d have to state clearly though that I’m not unconditionaly pro-RORB. But if that is the only way to teach them a lesson, then so be it. Please verify this. The law would only be in effect for 7 years? As in biblical number 7? But the way I see this, the actual demand for compulsory publishing of reply would be isolated cases if only they would allow public access to their “gates” for comments. Majority of public officials are not as onion-skinned as majority journalists (majority used twice for clarity).

I’m not out to defend Binay. For all I care, his ads are not entirely accurate either. To elaborate on that would be futile and a waste of space. But allow me to hammer this point into their minds. Let say the building in question is a property of a relative of the editor, and they want to tear it down to make way for a new project… Would the editor allow that writer to post that caption?

Ultimately, I’d need to ask for your PROFESSIONAL OPINION (no pun intended). Would you deem it responsible if it were your property? Let’s say you have a lot that was encroached by squatters and the project is already delayed by 5 years…

Reply: You’re right. The proposed measure’s effectivity is only seven years, which is more of a weakness than a strength. What is the basis for putting an end to something which legislators think is the best for media? This exposes the uncertainty that a right of reply law will bring about, a perception that is apparently acknowledged as early as now.

The point you raised about editors or reporters having an interest in a particular story is an ethical concern. If they have a conflict of interest, the readers should know about this. Journalists like me are obliged to make that disclosure. From my experience as a columnist, I do tell the readers openly anything that they should know about a personal stake in the topic I’m writing about.

For example, my column article on the Kadayawan festival in Davao last August had nothing to do with the workshop that I had conducted for the DOT and NCCA, but I felt duty-bound to make a disclosure nevertheless that both agencies took care of my plane fare and accommodation. This is to avoid the impression that I was in Davao on a personal capacity.

I do realize that not all journalists make disclosures, which is why we are trying our very best to conduct training on journalism.

Of course, the best way for a journalist to be true to his or her calling would be to avoid potential conflicts of interest. I hope this answers your questions.

I read your reply 5 times searching for an answer. Sensitive as the issue may be, and you being a journalist, I doubt that I would ever get a direct answer. I am not questioning your ethics. But because you mentioned “ethical concern”, I’d conclude that your professional opinion would echo my sentiments. The writer in question is unethical, irresponsible, a misfit who needs more training. Will you offer your services for free and try your very best to conduct a training on journalism at The Inquirer? Heaven forbid, they will only laugh at you.

In retrospect however, the caption “THIS IS THE WAY WE DO IT IN MAKATI” is a bit ambiguous. It can be viewed as taking pun at Binay’s slogan, or it can be viewed as insulting the tennants that they can’t get away with that in Makati. It’s just like the glass is half empty or the glass is half full. So either way, the writer can still make an excuse to his superiors in case they are the real owners of the said property. Clever thing, don’t you think?

You chose your reply very well, nothing to even slightly offend either side. To tell you the truth, you sound more like a priest. Except for the stand that you’re against RORB. There seems to be nothing concrete or profound on how to deal with the malpractices. Apart from those institutes, councils or whatever, which are far from being effective on the issue. What do you think would be a more viable alternative to the RORB?

Remember, we have an impatient population and very judgmental too. Time is not a luxury when you’re being accused. By the time the PPC decides to let the other party air their side, the issue would be too cold, the readers won’t even care. And the fact remains that an accusation that is not rebutted immediately would stay on, albeit vaguely in one’s memory, forever. “Ah, si Mayor so and so… may ginawa siya dati this and that… ambot, basta hindi mabuti… matagal na yon eh… alam mo naman hiha, binata po si lolo mo noon…hehe”

My sincere apologies if I’ve wasted your time. I’ll just leave this for you to ponder upon. But in case you value sensible discourse on any subject, you have my email address.

All the best Father Danny, all the best!

Reply: Don’t ever think that you’re wasting my time, and the fact that I’m replying right now means that I value intelligent comments from readers like you. If I sound like a priest in stating this point, so be it and I don’t take offense.

Perhaps I should be the one to apologize if I’m not so clear in pointing out two important things:

1. Failure to disclose any conflict of interest on the part of a journalist is unethical. With regard to the particular case you referred to, a reporter who has a relative in the demolished tenement has no business writing about the issue. And if assigned by the editor to do so, it is his or her responsibility to disclose such conflict of interest.

2. The alternative to RORB is to strengthen self-regulation in media. As I noted in our past exchanges, this is imperfect but this is the only way we can create an atmosphere that is conducive for freedom of the press. I also acknowledge that I might be vague in my discussion of self-regulation, since it is multi-pronged and involves the participation of not just the media organizations themselves but also the media audiences. The government, in a way, is also involved, but only in ensuring freedom of the press and avoiding any policies that will result in prior restraint and censorship. I agree that time is not a luxury for those who are accused, and it is possible that the PPC would have some delays in acting on complaints. But I’m sure you’re aware that an aggrieved party can opt to send their complaint to rival media organizations which would probably be more than willing to accommodate it. He or she may even disseminate the complaint on the Web which could be posted in blogs, discussion groups and e-groups. (Perhaps a more detailed discussion of self-regulation will be written in a future post, as this requires a kilometric discourse.)

As a last point, I seriously doubt if the Inquirer will ignore feedback from people like you and me. You should know that many of its editors and reporters are my friends. In fact, many of its reporters used to be my students at UP. From my experience, the ones I know are very open to criticism. Of course, I cannot say the same for the others I don’t know.

Right of Reply is not the solution. Tulad po ng sabi ninyo sa case ng PDI at kung hindi sila magpo-post ng replies, merong PPI para imbestigahan ang isyu. Baki hindi nalang bumuo ng mga organisasyon o palakasin ang kapangyarihan ng PPI at KBP para bantayan ang media (o gawing rule na dapat lahat under these organizations, etc). At least walang direct intervention mula sa mga pulitiko at ilang indibidwal.

Reply: Salamat sa komento. Mahirap talagang direktang makialam ang gobyerno dahil makokompromiso nito ang kalayaan sa pamamahayag. Lalong totoo ang argumentong ito kung susuriin ang kasalukuyang administrasyong alam nating itinuturing na “kaaway ng estado” ang mga kritikal na peryodista.

hi I’m doing my research regarding the right of reply bill please help me, what will be the possible effects if this bill will be implemented?

Reply: The possible effects if we were to have a “Right of Reply Law” could be summed up in two words: “Editorial Nightmare.” Journalists (especially editors) would find it hard to comply with the law. News media content is determined by the age-old elements of journalism and the Right of Reply Law is wont to add another element which is legal imposition, which is ironic if we consider that government claims to be on the side of press freedom.