N.B. – This was published in the July 2008 issue of the Philippine Journalism Review (PJR) Reports (pp. 11-12), the full text of which may also be retrieved from http://cmfr-phil.org/_pjrreports/2008/july/0708_story05.html.

Journalists are expected to refer to official sources of information in writing and producing their reports. There is, however, a potential failure in giving relevant information to their audiences if they were to rely solely on government-issued press releases and to accept hook, line and sinker the analyses that go with the data presented.

Journalists are expected to refer to official sources of information in writing and producing their reports. There is, however, a potential failure in giving relevant information to their audiences if they were to rely solely on government-issued press releases and to accept hook, line and sinker the analyses that go with the data presented.

That press releases are jokingly referred to as “praise releases” should prompt journalists to proceed with caution in citing the data and analyses they contain. While some writers of press releases try to be as factual as possible, one cannot deny that there are different ways of interpreting data and it is likely that the analysis will be done to favor the officials and offices concerned. In addition, the data presented could have been selected to achieve the same objective.

Social reality can be distorted not only by withholding the essential facts. There are also instances where all the data are made available to the public but presented in a manner hard to understand.

The National Statistics Office’s (NSO) report on the inflation rate for May 2008 is an interesting case study of how journalists should go beyond public pronouncements and to analyze carefully the publicly available data in the form of tables and charts.

The NSO press release dated June 5 provides in the first paragraph potential headline-grabbing information: “The year-on-year headline inflation rate at the national level further jumped to 9.6 percent in May from 8.3 percent in April, the highest inflation since January 1999 (10.5%). This was primarily triggered by the continuing higher annual price increases in the heavily-weighted food, beverages, and tobacco (FBT) index. The rest of the commodity groups also posted higher inflation rates during the month. Inflation a year ago was 2.4 percent.”

While journalists are expected to cite the figures and the official explanation behind the data, there is a need to relate the latter to pressing issues like the increases in the prices of rice and petroleum products.

The NSO press release more or less helps journalists in making the correlation as it gives a breakdown of increases in the FBT index. With regard to rice, “(a)nnual price adjustments were higher…at 31.7 percent in May from 24.6 percent in April” at the national level. In the case of the NCR, a “(h)igher annual price increase was noticed in rice at 43.6 percent in May from 38.4 percent in April.” As regards other regions, “(a)nnual price changes in rice posted in all the regions moved further higher…Inflation rate for rice…accelerated to 30.1 percent in May from 22.7 percent in April.”

Once a journalist gets updated statistics from the Department of Trade and Industry on the prices of rice and other commodities and includes these in his or her article, it would appear that the report is already complete. Proper contextualization, however, is still important in analyzing other important matters such as the effect of the series of oil price hikes on the country’s inflation rate.

Interestingly, the increases in gasoline, diesel, kerosene, and Liquefied Petroleum Gas (LPG) were only mentioned in the last few paragraphs of the NSO press release. It cited an increase in the fuel, light, and water (FLW) index by 0.7 percent nationwide, with NCR posting a 0.3 percent increase; and areas outside NCR, 1.0 percent.

Please note, however, that what was cited was a month-on-month comparison, which means that unlike the annual price adjustments in rice, the data compared were April 2008 and May 2008. The changes of prices are sometimes not noticeable on a month-on-month basis. The disparity can be better appreciated by using a year- on-year comparison, in this case between May 2007 and May 2008 data.

Missing figures

The year-on-year FLW index to which petroleum products belong was pegged at 8.2 percent nationwide as of May 2008. For NCR and areas outside NCR, the year-on-year figures were 6.6 and 9.0 percent, respectively. An astute observer may ask at this point: “Why were these figures not mentioned in the NSO press release?”

These and other important data are not explicitly stated in the press release, but they may be extrapolated by downloading the various multi-column inflation-related tables from the NSO website.

By computing the percentage increases on a year-on-year basis (i.e., the difference between May 2008 data and May 2007 data divided by the May 2007 data; and then multiplied by 100), one can come up with statistics even more newsworthy than what is stated in the official press release.

Analyzing the consumer price index (CPI) according to region, for example, a journalist would find out that 11 out of 17 regions had double-digit inflation, the highest being Region IX (Zamboanga Peninsula) with 13.5 percent. With the exception of Region XI (Davao) which had an inflation rate of 9.5 percent, all the other regions in Mindanao had double-digit inflation rates. The same can be said for all three regions in the Visayas.

The extrapolated data provide empirical evidence that increases in the prices of goods and services are felt in most provinces.

To make the inflation rate figures more relevant to the people, it is also necessary to present the purchasing power of the peso (PPP) based on the CPI figures (For basic information on the CPI and PPP, including how to compute the latter, please see my article “Reporting Inflation” published in the Philippine Journalism Review of June 2002, pp. 43-44).

In any case, computing the PPP based on the May 2008 CPI would show that one peso is worth only 65 centavos in real terms (See Table 1). This means that a person needs one peso today to buy goods and services worth only 65 centavos eight years ago (i.e., 2000 is the base year currently used by the government with regard to the CPI).

In any case, computing the PPP based on the May 2008 CPI would show that one peso is worth only 65 centavos in real terms (See Table 1). This means that a person needs one peso today to buy goods and services worth only 65 centavos eight years ago (i.e., 2000 is the base year currently used by the government with regard to the CPI).

A journalist may also add in his or her report that the value of the peso has been eroded by 35 percent (i.e., the difference between 1.00 and PPP multiplied by 100). Analyzing the regional data, one may also mention that ARMM has the lowest purchasing power of the peso (59 centavos) which translates to an erosion of its value by 41 percent (See Table 1).

The data serve as quantifiable proof of the complaint of underpaid workers that their wages are not enough to make ends meet.

Comparing the nominal and real value of the money people have today, a journalist could get updated statistics on wages from the Department of Labor and Employment and compute the real value of, for example, minimum wage earners in all regions. All s/he has to do is to multiply the nominal wage by the PPP of the respective region.

Low wages, low purchasing power

A careful scrutiny of the data would show a startling reality with regard to ARMM: it has the unfortunate distinction of having the lowest minimum wage (non-agriculture) and the lowest purchasing power.

Another angle worth reporting by journalists is the core inflation rate which, according to the NSO press release, was pegged at 6.2 percent in May 2008.

According to National Statistical Coordination Board (NSCB) Resolution 6 (series of 2003), core inflation is the “year-on-year rate of change of the monthly headline CPI after excluding food and energy items.” To be more specific, core inflation is based on the headline inflation and excludes the following items which account for 20.2 percent of the CPI:

- Rice (11.82 percent);

- Corn (1.23 percent);

- Fruits and Vegetables (5.35 percent);

- LPG (0.68 percent);

- Kerosene (0.40 percent); and

- Oil, gasoline, and diesel (0.72 percent).

Theoretically, the difference between the headline and core inflation rates should be negligible if the economy were stable. The computation of the core inflation rate, after all, leaves out of the equation what the NSCB described as “transient disturbances” on the CPI. In the context of the country’s economic situation, these refer to the sudden increases in the prices of rice and petroleum products.

The core inflation rate can be useful in assessing the impact of monetary policy. According to NSCB, it can provide “a better gauge of the overall state of the economy and a more reliable basis for economic policymaking.”

That the May 2008 core inflation rate of 6.2 percent is lower than the headline inflation rate of 9.6 percent should not be easily dismissed as a result of simply excluding six items from the computation. A journalist should carefully analyze the core and headline inflation rates through the years (See Table 2).

That the May 2008 core inflation rate of 6.2 percent is lower than the headline inflation rate of 9.6 percent should not be easily dismissed as a result of simply excluding six items from the computation. A journalist should carefully analyze the core and headline inflation rates through the years (See Table 2).

In 2005 and 2006, the difference between headline and core inflation rates was less than one percentage point; and in 2007, no difference at all. What proves to be remarkable in May 2008 is the 3.4-percentage point difference. This indicates that the current price fluctuations of excluded items in the core inflation rate, particularly rice and petroleum products, are steeper and more sudden than in the past three years.

The challenge therefore remains for journalists to deeply analyze the official data. Contextualization remains the key to making stories relevant to the audiences, and they deserve no less from journalists whose mandate is to help shape public opinion.

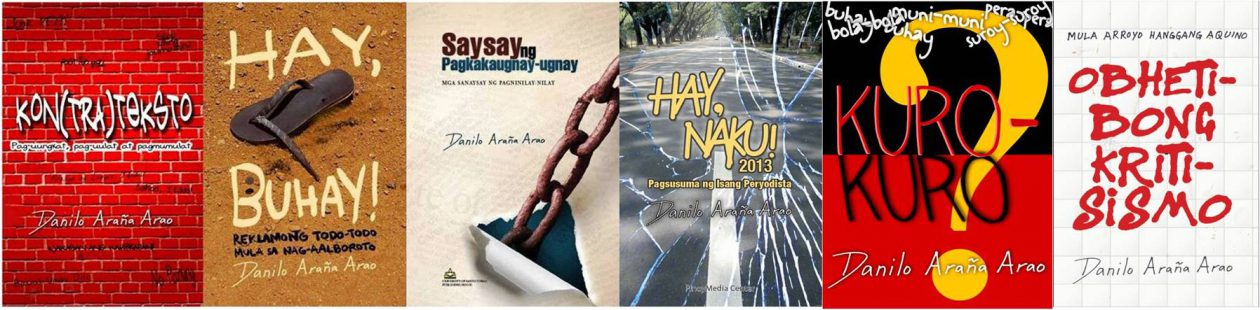

Danilo Araña Arao is an assistant professor of journalism at the University of the Philippines College of Mass Communication where he is concurrent director of the Office of Research and Publication. He is managing editor of the Philippine Journalism Review (PJR), the refereed journal publication of the Center for Media Freedom and Responsibility.